One day, a mother returns home to find that

her children are missing. She looks and

she looks, they are nowhere to be found, so she leaves to search for them. She travels far, looking everywhere; she searches for

so long that she becomes lost. Distraught, starving, her cries are heard from miles around, but no one comes. In the absence of hope, she dies.

This woman is known in myths from early on

in the world: She is Demeter, Goddess of Life and Death, she is La Llorona, she is Niobe, she is she

is the woman in white.

Except now, she will be reborn, and she will have

revenge.

*

The story of La Huesera is not mine to tell. I will say, however, that I believe in

ancestral memory, in the collective spirit of women, and the wisdom left behind

from all who have walked the earth, since in the beginning. The history of the world is woven in to the

very helices of our DNA. Do you still

hear it sometimes? I can say that I knew,

even as a little girl, that my bones carried memories with origins long before

their time. The ways of the old world

are still among us, but they are hidden.

You can find them only in places people have left untouched.

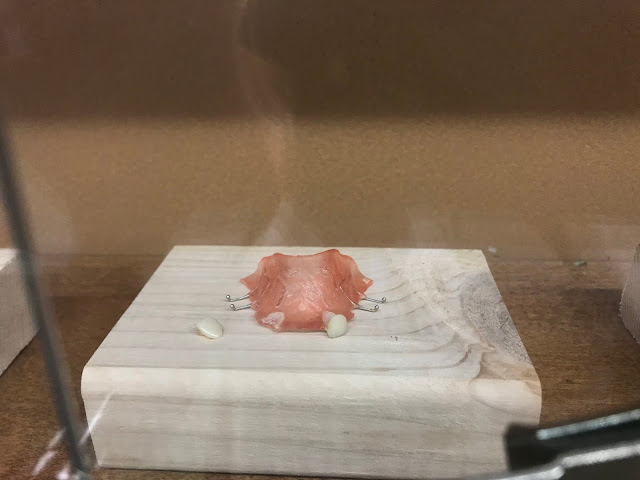

La huesera means Bone Woman, though she has many

other names. I imagine her as the slow

hands of transformation, she stokes the fire and raises a phoenix, she pulls forth what is reborn from ashes only after setting

itself aflame. She does not answer

prayers, she does not come when called. She

appears only after all hope is lost. She is the

bone gatherer. An ancestral

aggregator. Keeper of the keys. She creates new life from what remains after everything else has died

and fallen away.

Nothing borrowed, nothing

owed.

*

Robins are said to

symbolize renewal and new birth. They were always amongst the first migrating

birds to return at the end of winter to the trees outside of my childhood home

in Virginia Beach. Adults, red-breasted

with charcoal coats and fluffy white butts, would sing to each

other from powerlines and across the sky as soon as the sun peeked

over the edge of the horizon. I'd see twigs and trash scraps begin aggregating, their nests slowly transform, and then one day - pop! Four to six little blue eggs in the nest. Robin's eggs are a unique shade

of blue – a kind of cyan, a kind of turquoise – sometimes speckled but, more

often than not, you don’t roll them over to find out because if you touch them,

the mother might not come back to the nest.

Or so my Dad told me.

I remember

watching a mama robin pull an earthworm up from the damp, soggy, early morning

ground, swallow a little, actually regurgitate, chew it up, and then take it back to feed the little

ones. When they were old enough to learn

how to fly, there was, every year, at least a bird or two that just didn’t make

it. I had never seen them fall, but their carcasses would sit until the evening, when they would be ripped apart by cats and by morning, have ants crawling out

of their eyes, left to rot on the ground beneath the nest where the others cried the

morning after, waiting for their mother to return.

Until I started burying their bodies next to each other along the fence of our backyard.

*

“You can’t keep

them as pets,” my Dad told me one day, “pets are animals that we feed and keep

alive.” He was trying to be funny but I was inconsolable. The first set of bones I brought

home were those of one of the many fallen baby robins. Something had dug one of the graves up and

ripped one of its wings off. I cried and

cried and cried, but my Dad remained unwavering.

I wanted to keep the bones, but instead, I started a

fire. I understood that the only honor

there was in death was the way in which the living honored the lives that had passed

before them, so I took my journal, the gasoline can from the garage and a matchbox

and went back into the backyard with the bones.

I dug a single square-foot hole with a shovel too big for my small

hands, and I placed what remained of the baby robin’s body inside of it. I collected twigs, just like the bird’s

mother would have, and I built a temple of twigs around what remained of the body. I gave the bird a name, wrote a short eulogy, and

preached my first sermon about the meaning of life so quietly that only the bones could hear. I placed my note at

the foot of the temple, poured out a little gasoline, lit the match and tossed it in. First, the stench of sulfur filled the air, then, the acrid smell of turpentine. The rising black smoke snaked into the sky as

the twigs caught fire and the gasoline burned off. I watched the smoke turn grey and continue to

rise as the sun set from the window of my room after I had gone back

inside and collected what remained of the

bones the next morning to bury them again.

*

Many of the bones

I have found carry stories that are not mine to tell. Some already lived second lives and have

since been laid back to rest. I can tell

you, however, that while I have always been a collector of sorts, many of the

things I found feel as if they found me. I know when it is best to leave something as

it is and when it should be retrieved. I

know that even bones occasionally get lonely.

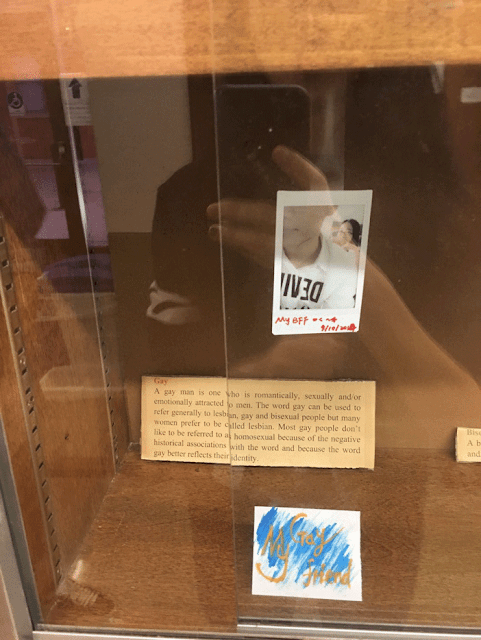

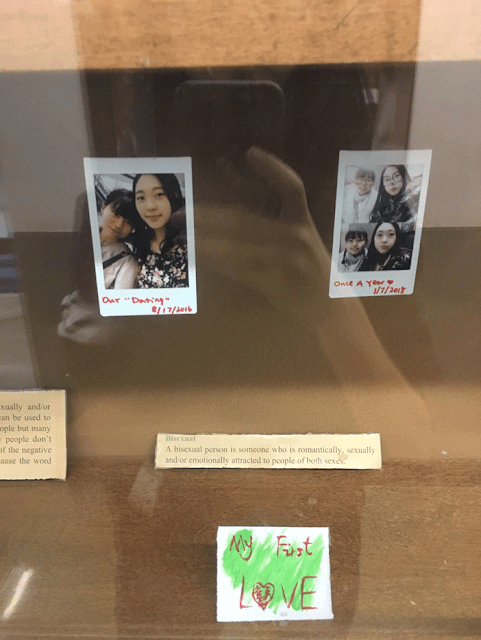

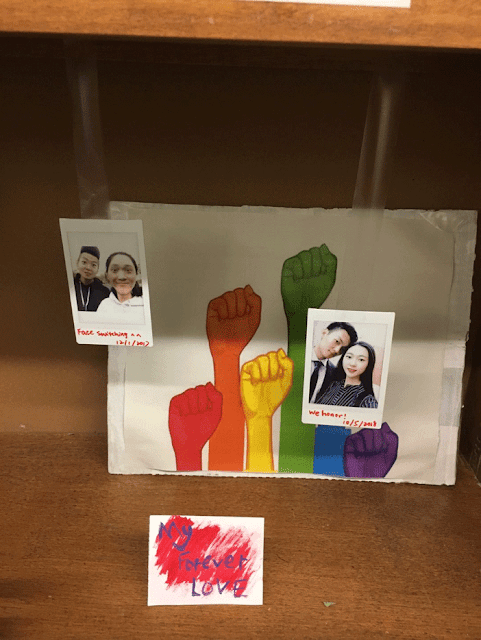

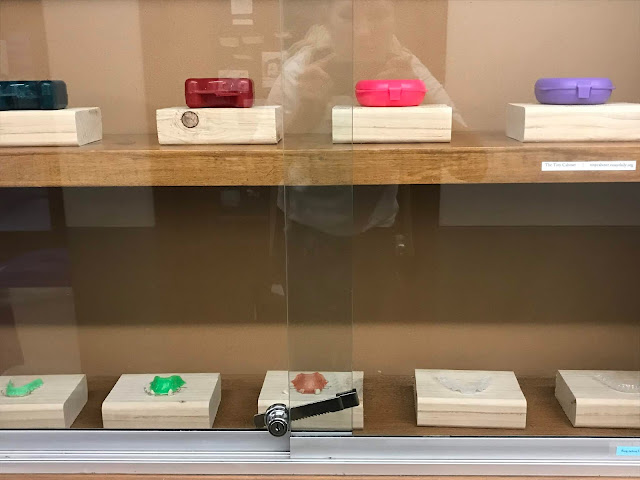

They are – the things I have collected – among other things, brief

snapshots of time. They are images that

are present in all things. They represent what

came before, what may remain behind. Something perfectly preserved. Brief snapshots of time, in stamps and coins, flowers and

bones, seeds and leaves. Things that have a story. Inside of them are the remains of an entire universe - life that has been and gone.

*

Go and gather the bones, girl.

Gather everything together. Make something from the ashes.

From the earth. From the wind. From the water. From the fire.

You are life. You are the slow hands of time.

You know what came before. You know what comes after.

The beginning and the end.

Listen, girl. Listen better.

The bones know.

The bones remember.